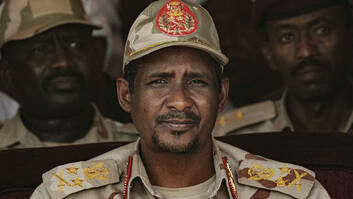

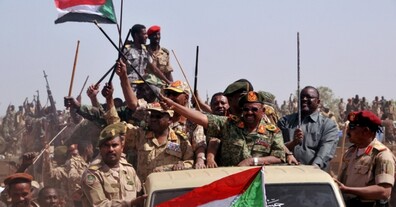

Rapidly escalating Conflict erupts in Sudan Fighting has erupted in the capital city of Sudan, Khartoum, and across the North African country as powerful rival military factions and their international backers battle for control of this strategic region, its resources and its future. The sudden slide into violence between the Sudanese army and a paramilitary group called Rapid Support Forces (RSF) stranded thousands of foreigners, including diplomats and aid workers in the country, with the UK, US, France, Germany, Italy, Greece, Egypt, India, Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states among those closing embassies and racing to evacuate their nationals.  Refugee Crisis So far, more than 450 people have been reported killed in the conflict and another 4,000 wounded, according to the World Health Organisation. UN estimates suggest that some 75,000 people have been displaced following the outbreak of fighting, which has also led to foreign workers leaving the country en masse. The capital, Khartoum, a city of 4 million people, is reported to be suffering widespread outages of electricity, as well as food and water shortages. At least 20,000 Sudanese have fled to Chad, while 4,000 South Sudanese, who are part of the 1.1 million refugees hosted by Sudan from neighbouring countries, have been forced to return home, according to the UNHCR. The United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) reported on Wednesday that the current number of 3.7 million internally displaced people in Sudan is rapidly increasing.  A 72-hour ceasefire was declared to allow for the evacuations of foreigners to take place, with negotiations currently underway to extend its duration. British families caught up in the fighting had initially accused the UK government of “abandoning” them, despite reassurances from prime minister Rishi Sunak and the Foreign Office that talks were underway to bring them home.  After the truce was agreed between the two factions, the UK was able to airlift 536 citizens to safety, with foreign secretary James Cleverly now urging British nationals who may be “hesitant” or “weighing up their options” to make their way to Wadi Seidna, where there are “planes and capacity” in place to get people out. Alicia Kearns, chair of the Commons Foreign Affairs Committee, told BBC Radio 4’s Today programme that the number of British people hoping to be evacuated could total “3,000, 4,000 plus”, adding that those on the ground were living in “abject fear”, had little food and water left and, in some cases, had even been reduced to killing their pets “because they’re worried they’re going to starve!”  What is going on in Sudan? Tension had been building for months between Sudan’s army and the RSF, which together toppled the civilian transitional government in an October 2021 coup. The friction in Sudan was brought to a head by an internationally-backed plan to launch a new transition with civilian parties. A final deal was due to be signed earlier in April, on the fourth anniversary of the overthrow of long-ruling dictator, Omar al-Bashir, in a popular uprising.  Both the army and the RSF were required to hand over power under the plan and two issues proved particularly contentious: one was the timetable for the RSF to be integrated into the regular armed forces, the second was when the army would be formally placed under civilian oversight.  When fighting broke out on 15 April, both sides blamed the other for provoking the violence. The army accused the RSF of illegal mobilisation in preceding days and the RSF, as it moved on key strategic sites in Khartoum, said the army had tried to seize full power in a plot with Bashir loyalists.  The protagonists in this power struggle are General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, head of the Sudan army and leader of Sudan’s ruling council since 2019 and his deputy on the council, RSF leader General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, commonly known as Hemedti. As the plan for a new transition developed, Hemedti alligned himself more closely with civilian parties to form a coalition, the Forces for Freedom and Change (FFC), that had shared power with the military between Bashir’s overthrow and the 2021 coup.  Diplomats and analysts said this was part of a strategy by Hemedti to transform himself into a statesman. Both the FFC and Hemedti, who grew wealthy through gold mining and other ventures, stressed the need to sideline Islamist-leaning Bashir loyalists and Jihad veterans who had regained a foothold following the coup and have deep roots in the army. Along with some pro-army rebel factions that benefited from a 2020 peace deal, the Bashir loyalists opposed the deal for a new transition to civilian rule.  What is at stake? The popular uprising had raised hopes that Sudan and its population of 46 million could emerge from decades of Islamicist dictatorship, oppressive sharia rule, internal conflict, civil war and economic isolation under Bashir. This renewed and rapidly escalating Conflict could not only destroy all those hopes, but destabilise a volatile region bordering the Sahel, the Red Sea and the Horn of Africa. It could also play into competition for influence in the region between Russia and the United States and between regional powers who have courted different factions in Sudan.  The Geostrategic Situation Western powers, including the US and the UK, had swung behind a transition towards democratic elections following Bashir’s overthrow. They suspended financial support following the coup, then backed the plan for a new transition toward a civilian government. Energy-rich powers Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates have also sought to shape events in Sudan, seeing the transition away from Bashir’s rule as a way to roll back Islamist influence and bolster stability in the region. Gulf states have pursued investments in sectors including agriculture, where Sudan holds vast potential and ports on Sudan’s Red Sea coast. Russia has been seeking to establish a naval base on the Red Sea, while several UAE companies have been signing up to invest, with one UAE consortium inking a preliminary deal to build and operate a port and another UAE-based airline agreeing with a Sudanese partner to create a new low-cost carrier based in Khartoum.  Burhan and Hemedti both developed close ties to Saudi Arabia after sending troops to participate in the Saudi-led operation in Yemen. Hemedti has struck up relations with other foreign powers including the UAE and Russia. Egypt, itself ruled by military general President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi who overthrew his Islamist predecessor, has deep ties to Burhan and the army and recently promoted a parallel track of political negotiations through parties with stronger links to the army and to Bashir’s former government.  What could happen? International parties have called for a ceasefire and a return to dialogue, but there has been little sign of compromise from the warring factions. The army has branded the RSF as a rebel force and demanded its dissolution, while Hemedti has called Burhan a criminal and blamed him for visiting destruction on the country.  Though Sudan’s army has superior resources including air power, the RSF has expanded into a formidable force estimated at 100,000 men that has deployed across Khartoum and its neighbouring cities as well as in other regions, raising the spectre of protracted conflict on top of a long-running economic crisis and existing, large-scale humanitarian needs. The RSF can also draw on support and tribal ties in the western region of Darfur, where it emerged from the militias that fought alongside government forces to crush rebels in a brutal war that escalated after 2003.  The RSF has a controversial past The Rapid Support Forces are the preeminent paramilitary group in Sudan. Their leader, Dagalo, enjoyed a rapid rise to power. During Sudan’s Darfur conflict in the early 2000s, he was the leader of Sudan’s notorious Janjaweed forces, implicated in human rights violations and atrocities. An international outcry saw Bashir formalize the group into paramilitary forces known as the Border Intelligence Units.  In 2007, its troops became part of the country’s intelligence services and, in 2013, Bashir created the RSF, a paramilitary group overseen by him and led by Dagalo. Dagalo turned against Bashir in 2019, but not before his forces opened fire on an anti-Bashir, pro-democracy sit-in in Khartoum, killing at least 118 people.  He was later appointed deputy of the transitional Sovereign Council that ruled Sudan in partnership with civilian leadership.According to Sudanese and regional diplomatic sources, Russia’s mercenary group, Wagner, has involved itself in the conflict by boosting the RSF’s missile supplies.The sources said the surface-to-air missiles have significantly buttressed RSF paramilitary forces under Dagalo. CNN claims that satellite imagery supports these claims, showing an unusual uptick in activity on Wagner bases, in bordering Libya, where a Wagner-backed rogue general, Khalifa Haftar, controls swathes of land. The bolster in support comes amid deepening ties between Moscow and Sudan’s military leadership  Is this another Proxy War between America and Russia? A July 2022 investigation found that Sudan’s military leaders granted Russia access to the east African country’s gold riches in exchange for military and political support. Dagalo’s forces were a key recipient of Russian training and weaponry, and Sudan’s military leader Burhan is also believed by CNN’s Sudanese sources to have been backed by Russia, before international pressure forced him to publicly disavow the presence of the Russian mercenary group Wagner, in Sudan.  The two rivals mirror each other Burhan is essentially Sudan’s leader. At the time of Bashir’s toppling, Burhan was the army’s inspector general. His career has run an almost parallel course to Dagalo’s. He also rose to prominence in the 2000’s for his role in the dark days of the Darfur conflict, where the two men are believed to have first came into contact. Al-Burhan and Dagalo both cemented their rise to power by currying favor with the Gulf state powerhouses. They commanded separate battalions of Sudanese forces, who were sent to serve with the Saudi-led coalition forces in Yemen. Now they find themselves locked in a power struggle. Which several observers believe is actually a proxy war between America and Russia using factions within Sudan to serve the interests of multinational companies and their globalist agenda.  Sudan’s regional, economic and strategic importance Sudan is located at a geographically critical region . It borders Egypt and Libya in North Africa, Ethiopia and Eritrea in the Horn of Africa, the East African nation of South Sudan, and Central Africa’s Chad and the Central African Republic. Sudan is the site where the White and Blue Nile Rivers merge to form the main Nile and is home to more than 60% of the Nile River Basin. Safe management of the Nile’s water is crucial for stability of the region. Northern neighbour Egypt is 90% dependent on the Nile river for its water supply, while Ethiopia to the east is looking to double the country’s electricity generation through the construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam. The project has been a source of contention, though – Ethiopia began filling the dam in 2020-2021 without an agreement with Egypt, and last year Egypt protested Ethiopia’s planned third filling of the dam to the U.N. Security Council. The United Nations has called on the three nations to negotiate a “mutually beneficial” agreement over the Nile’s management – something that will be difficult should Sudan fall into a prolonged period of instability. Sudan also has a strategic location on the Red Sea, a body of water that approximately 10% of global sea trade passes through, with the Suez Canal connecting Asian and European markets. And then there are Sudan’s immense mineral resources. The nation is Africa’s third-largest producer of gold, has major oil reserves and produces over 80% of the world’s gum arabic – a component of food additives, paint and cosmetics.  Sudanese gold, War against Russia As a result of this strategic and economic importance, Sudan has attracted competing international partners. Gulf oil states Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, for example, saw Bashir’s ouster as a chance to stabilize the region and invest in everything from agricultural projects to Red Sea ports.  For the background to this conflict, Read : Faith Under Fire in Sudan https://www.christianlibertybooks.co.za/item/faith_under_fire_in_sudan__hc And Frontline - Behind Enemy Lines for Christ Dr. Peter Hammond Frontline Fellowship PO Box 74 | Newlands | 7725 | Cape Town | South Africa Tel: +27 21 689 4480 website | email To view our Frontline PRIORITY PROJECTS for PRAYER and ACTION with pictures, click here https://www.frontlinemissionsa.org/donate-to-frontline-fellowship---south-africa.html See also related articles: Sudan in Crisis at a Crossroads Understanding Islam – Evangelising Muslims The Nuba Mountains for Christ An Overview of Sudan in History Genocide in the Nuba Mountains of Sudan Freedom Vote for Southern Sudan Sudan Closes Schools, Confiscates Property and Expels Foreign Christians A Different Kind of War Jihad Against Christians in Africa Christians Under Fire in Africa Persecution Explodes as Muslims Come to Christ Pray for Christians Under Fire in Nigeria and Sudan Urgent Call for Prayer for Christians Under Fire in Africa South Sudan Celebrates Successful Struggle for Secession Sudan Government Destroys Churches and Attacks Bible College in Khartoum Southern Sudan Referendum on Secession Christians Targeted in the Nuba Mountains of Sudan Dr. Peter Hammond is the author of Faith Under Fire in Sudan. Peter Hammond has travelled throughout the war-devastated Nuba Mountains, an island of Christianity in a sea of Islam, showing the Jesus film in Arabic, proclaiming the Gospel, training pastors and evading enemy patrols. Peter has conducted over 1,200 meetings inside Sudan.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

"And Jesus came and spoke to them, saying, “All authority has been given to Me in heaven and on earth.

Go therefore and make disciples of all the nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit,

teaching them to observe all things that I have commanded you; and lo, I am with you always, even to the end of the age.” Amen.” Matthew 28: 18-20

Go therefore and make disciples of all the nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit,

teaching them to observe all things that I have commanded you; and lo, I am with you always, even to the end of the age.” Amen.” Matthew 28: 18-20

|

P.O.Box 74 Newlands 7725

Cape Town South Africa |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed