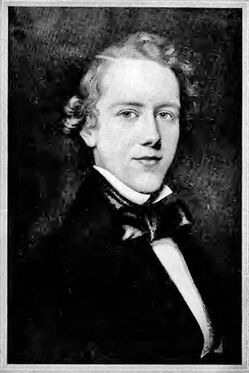

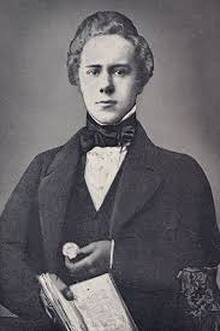

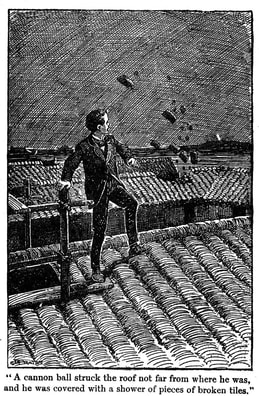

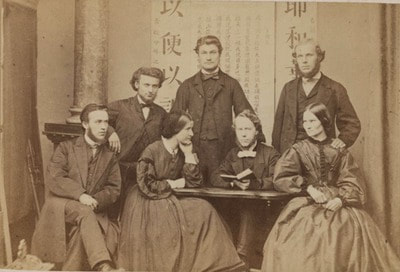

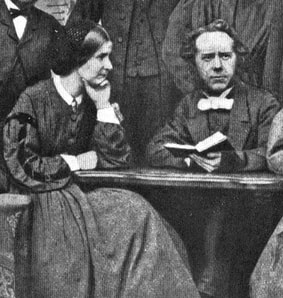

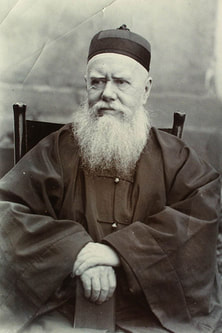

To Listen to an Audio Presentation of this Article Click Here Consecrated Hudson Taylor’s father, James Taylor, before his birth, knelt beside his 24 year old wife, Amelia, in the parlour at the back of his busy chemist shop in Yorkshire, England, and prayed: “Dear God, if you should give us a son, grant that he may work for You in China.” Deviated By age 4, Hudson would declare: “When I am a man, I mean to be a missionary and go to China.” Also by age 4, he had learnt the Hebrew alphabet. Hudson was home-educated and grew up in a Godly home. However, by age 17, he was severely backslidden, restless and rebellious against his parents.  Converted In June 1849, when he was 17, his mother locked herself in the room 50 miles from where Hudson Taylor was, and determined to pray that her son would become a Christian and that she would not leave the room until she was sure that her prayers had been answered! That same afternoon, Hudson Taylor picked up a Gospel tract and was struck by the phrase: “The finished work of Christ.” “Light was flashed into my soul by the Holy Spirit. There was nothing to be done but to fall down on my knees and pray for salvation.” As he rushed breathlessly to tell his mother of how he had been “born again” she interrupted him and told him that she already knew! Conviction Hudson Taylor wrote of the “intense longing for God” that gripped him: “From that time, the conviction never left me that I was called to China.” Immediately, he began to prepare himself by studying Chinese through a copy of Luke’s Gospel in Mandarin. He denied himself comforts and imposed disciplines on himself to prepare himself for the mission field. He undertook work amongst the poor and the sick, and read avidly on China. He also threw himself into studying Latin, Greek, Theology and Medicine.  Preparation Hudson immersed himself into the Bible and prayer, including an entire night of intense prayer. One word came to characterise Hudson Taylor – faith. He determined to trust in God alone for all his needs. He loved to give to God and so tithing was soon left far behind as he gave away two-thirds of his income. His maxim became: “See if you can do without.” His concern for China grew into an overwhelming burden and he felt as though Christ’s compassion for the multitude was flooding his soul. Shattering Meeting a missionary to China, Hudson excitedly told him of his plans. This missionary discouraged him, telling him that the Chinese would never receive him on account of his fair hair! (Later while trying to dye his hair black, Hudson was injured and almost blinded when the ammonia mixture exploded the glass bottle it was mixed in!) Conflict In 1853, as the Taiping rebellion broke out, Hudson Taylor, just 21 years old, said an emotional goodbye to his mother and sailed from England. The journey by sea took six months, and included a severe storm. By the time that Hudson Taylor landed in Shanghai in 1854, the rebels held the city and 50,000 Imperial soldiers besieged it. Horrific sights and sounds greeted him. China was passing through an immense upheaval. There were several major uprisings in China in the 1850s and the 1860s, two of them resulting in 25 million dead. Another 10 million died in the years 1877 to 1879, during a famine in the North of the country. There were also wars between China and Britain, France, Russia and Japan. It hardly seemed the time to launch a new mission into China, but Hudson Taylor was gripped by the fact that some 380 million people in the vast interior of China had never seen a Westerner, nor heard the Name of Christ. He determined to change that.  Under Fire The house Hudson was staying in, in Shanghai, was struck by gunfire and the house next door to his was destroyed. Nevertheless, he gave himself to the study of the language, to evangelism and to helping the victims of the war. During these fearsome upheavals, Hudson travelled to take the Gospel to previously un-evangelised areas. One of these trips was a 200 mile journey up the Yangtse River. He frequently witnessed people being beheaded and himself came very close to being lynched on occasion. William Chalmers Burns It was during this time that he developed a brief, but deep, friendship with William Chalmers Burns, and they determined together to adopt Chinese dress. Burns and Taylor were men of one heart and mind. They stayed at Swatow, a centre of the opium trade and “the most wicked place imaginable.” Burns was taken prisoner during their time in Swatow. An Indigenous Approach Hudson Taylor’s decision to shave his head and adopt Chinese dress was rooted in his deep respect for Chinese culture and his view of the role of the missionary. Many Chinese objected to Christianity, he argued, because it seemed to be a foreign religion. His decision was greeted with derision and contempt by most Westerners. For his part, Taylor thought many of the missionaries to China were worldly, lacking in dedication and ineffective.  Courtship and Marriage Hudson Taylor, whose proposals for marriage had already been rejected by two women in England, then met and courted a missionary teacher, Maria Dyer, the much sought after, 20 year old daughter of prestigious missionary parents. The missionary establishment were horrified at this “unsophisticated” missionary who had “gone native” wearing Chinese dress and opposed the marriage. However, Maria showed herself to be of equal dedication to Hudson and on 20 January 1858, Hudson Taylor and Maria Dyer became husband and wife. It was to be an uncommonly happy marriage, lwargely because they shared the same deep passion to evangelise China at great personal sacrifice. Defeat and Retreat From the start they were frequently in danger and their first child, Grace, was born with a riot raging outside. Hudson’s missionary partner, Dr. Parker, who had opened a clinic at Ningpo, was compelled to return to Scotland when his wife died. With supplies dwindling, and Hudson’s health deteriorating, he had to make the painful decision to close the medical clinic and return to England. There he was to remain for six years. But this temporary retreat proved to be the precursor of a great missionary advance. Burdened in Prayer His burden for inland China was becoming overwhelming and the only relief he could find was in prayer and the Word of God: “First earnest prayer to God to thrust forth labourers, and second, the deepening of the spiritual life of the Church, so that men should be unable to stay at home”, wrote Hudson.  Without a Vision a People Perish In 1865, Hudson dictated a book “China, its Spiritual Need and Claims” to Maria, while he restlessly paced the floor. One paragraph declared: “Can all the Christians of England sit still with folded arms, while these multitudes in China are perishing, perishing for lack of knowledge, the lack of that knowledge which England possesses so richly, which has made England what England is, and made us what we are? What does the Master teach us? Is it not that if one sheep out a hundred be lost, we are to leave the ninety and nine and seek that one? But here the proportions are almost reversed, and we stay at home with the one sheep and take no heed to the ninety and nine perishing ones!” Doubt Hudson knew that a new missionary organisation dedicated to the evangelisation of inland China was needed, but at this point he found himself racked with doubt. He rarely slept for two hours at a time. He agonised over the desperate spiritual plight of China, and with what he called his “unbelief.” He feared taking responsibility for sending young men and women into the interior of China where they would be subjected to rejection, illness and severe persecution. He thought that he was on the verge of a nervous breakdown. He wrote: “For two or three months, intense conflict …thought I should lose my mind.” Agony One Sunday morning, he slipped out of Church after worship “unable to bear the sight of a congregation of a thousand or more Christian people rejoicing in their own security, while millions are perishing for lack of knowledge.” He wrote that he wandered out on the sands of Brighton Beach, “alone in great spiritual agony.” Full Surrender But, during this prayer walk “the Lord conquered my unbelief and I surrendered myself to God for this service. I told Him that all the responsibility …must rest with Him; that as a servant it was mine to obey and to follow Him …His to direct, care for and to guide me and those who might labour with me….”  China Inland Mission Immediately he wrote in the margin of his Bible: “Prayed for 24 willing, skilful labourers, Brighton, June 25 1865.” The China Inland Mission that Hudson now planned to launch was innovative and radical for the time. Hudson Taylor launched the first truly interdenominational faith mission. Revolutionary Strategy From the first, Taylor determined that the China Inland Mission would have six distinctive features: (1) Its missionaries would be drawn from any denomination, provided that they would sign its evangelical, Protestant doctrinal statement; (2) CIM missionaries would receive nosalaries, but trust in the Lord to supply their needs. Income would be shared, no debts would be incurred; (3) No appeals for funds would be made; (4) The work abroad would not be directed by the home committee, but by himself, and eventually other leaders, in the field, in China; (5) The organisation would press on into the interior of China “where Christ has not been named”; (6) The missionaries would wear Chinese clothing and worship in Chinese style buildings. In addition, CIM would use lay workers rather than ordained ministers, and it would even accept single women as missionaries. For the time, all this was radical. Volunteers Within the year, Hudson and Maria Taylor and their four children set sail for China with 16 young missionaries on board. Soon there were 24 CIM missionaries in China. God’s blessings on this new enterprise were soon evident, with 20 of the ship’s crew making commitments to Christ during the voyage.  Dissension But, within the year, the new mission was engulfed in opposition, dissension, controversy, fire and death. In 1867, their daughter, Grace, died. Their mission house in Yangchow was attacked and set on fire. Furious persecution engulfed them. As Hudson Taylor wrote: “If the Spirit of God works mightily, we may be sure that the spirit of evil will also be active.” Dedication Undeterred, Hudson treated more than 200 patients each day, with one of his converts, Tsiu, preaching to those waiting for medical treatment. Hudson made enormous demands on himself and expected equally high standards from his CIM missionaries. Disruption One of his new missionaries, Louis Nicol, grew increasingly bitter and resentful of Taylor’s style of leadership, and spent his time visiting other missionaries and grumbling. Louis Nicol soon abandoned the Chinese dress, claiming that the English clothes gave him more protection and respect. “I will not be bound neck and heel to any man!” he declared. After nearly two years of unpleasantness and disruption, Hudson regretfully dismissed Nicol from the mission, mainly for unrelenting slander and lies. Three CIM missionaries resigned in sympathy with Nicol.  Criticism At around the same time, two other CIM missionaries complained that it was dangerous for so many unmarried men and women to live together at New Lane, the CIM headquarters in China, and they accused Hudson of being too familiar with the young ladies (Hudson and Maria kissed some of the girls on the forehead before they went off to bed). The ladies themselves denied any inappropriate behaviour, but still the complaint reached London and for a time led to a fall in support for the mission. In spite of constant controversies, the number of CIM missionaries grew, in time becoming the largest mission organisation in the world. Controversy Then Timothy Richard, a Welsh Baptist, began to cause further divisions within the CIM, arguing that God also works through other religions such as Confucianism, Buddhism and Taoism. A handful of CIM missionaries were influenced by Richard’s liberal views and left the mission. As Hudson began sending unmarried single women into the interior, another storm of controversy and criticism erupted. Courage The courage of these tenacious young pioneers cannot be exaggerated. Annie Royle Taylor (no relation to Hudson), one of the many bold individualists who joined CIM, set her sights on taking the Gospel to the forbidden city of Lhasa in the heart of Tibet. She adopted native Tibetan dress and shaved her head in the fashion of a Tibetan nun. Bandits stole her tent and clothing and killed most of her pack horses. Some of her workmen died, others turned back. One of her Chinese workers demanded more money and when that was refused, he brought accusations against her to the Tibetan authorities, which led to her arrest. Tibet Annie Taylor finally established her own agency, the Tibetan Pioneer Mission, recruiting 14 missionaries to work with her, but in less than a year, all had left her and the infant mission was in shambles. However, Annie Taylor continued for more than 20 years, working mostly alone in Tibet.  Missionary Commitment Hudson Taylor did not make a distinction between married and single women. He expected married women to focus primarily on ministry, even as their single sisters did. To male recruits he wrote: “Unless you intend your wife to be a true missionary, not merely a wife, homemaker and friend, do not join us.” Maria set the pace for the other married women in the mission, caring for five children and actively reaching out to the Chinese women in daily outreach. Death in the Field In 1870, the Taylor’s son Samuel, died, and then their fifth son, Noel, died two weeks after being born, and then, a few days later, Maria Taylor died at age 33. Four of Maria’s eight children died before they could reach age 10. Determination Hudson returned to England, married Jennie Faulding, and suffered an accident, which left him with a damaged spine. But, even while recovering and immobile, he refused to be idle. Prayer and planning filled his time: “China is not to be won for Christ by quiet, ease-loving men and women …the stamp of men and women we need is such as will put Jesus, China and souls, first and foremost in everything, and at every time, even life itself must be secondary.” As someone who had literally given all to Christ in China, he found it impossible to expect any lesser commitment from others. Steadfast Hudson was frequently accused of being demanding and autocratic, but in his mind he was merely anxious to protect the integrity of the Mission. In spite of constant poor health, regular bouts of depression, and his self-confessed irritation and impatience, he also could show tremendous flexibility and steadfastness under trial.  Wholehearted Hudson and Jennie Taylor presented an incredible example of dedication. When they were bequeathed several thousand pounds, they gave it all to the Mission. They were frequently separated from one another and engaged in demanding journeys and a relentless schedule of ministry. Still, Hudson could declare at the end of his life that “the sun had never risen upon him in China without finding him at prayer.” Faith There was an urgency in everything that he did. He was a man of faith, who stated that his life was based upon three facts: “There is a living God. He has spoken in the Bible. He means what He says and He will do all that He has promised.” A Soldier for Christ In a letter to his mother, Hudson described his own assessment of his life in these words: “Envied of some, despised by many, hated perhaps by others; often blamed for things that I never heard of or had nothing to do with; an innovator on what have become established rules of missionary practice; an opponent of mighty systems of heathen error and superstitions; working without precedent in many respects and with few experienced helpers; often sick in body, as well as perplexed in mind and embarrassed by circumstances; had not the Lord been specifically gracious to me, had not my mind been sustained by the conviction that the work is His, and that He is with me in …the thick of the conflict, I must have fainted and broken down. But the battle is the Lord’s and He will conquer. We may fail, do fail continually, but He never fails.” China for Christ Indeed, by the end of Hudson’s life, the very mission organisations that had belittled and ridiculed his methods had begun adopting many of them. By the time Hudson Taylor died, there were 205 CIM mission stations, 849 missionaries and 125,000 Chinese Christians. Today there are over 120 million Christians in China. “After these things I looked, and behold, a great multitude which no one could number, of all nations, tribes, races and tongues standing before the Throne and before the Lamb ...” Revelation 7:9  Dr. Peter Hammond Frontline Fellowship P.O. Box 74 Newlands 7725 Cape Town South Africa Email: [email protected] This article was adapted from a chapter of The Greatest Century of Missions book (224 pages with 200 photographs, pictures, charts and maps), available from Christian Liberty Books, PO Box 358 Howard Place 7450 Cape Town South Africa Email: [email protected], Website: www.christianlibertybooks.co.za.

2 Comments

Janet Martin

22/5/2019 02:26:38

That was an excellent article on Hudson Taylor.

Reply

Deon Goosen

22/5/2021 08:43:41

These people if great faith has truly been real trailblazers! Their work is blessed even now.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

More Articles

All

Archives

December 2022

|

"And Jesus came and spoke to them, saying, “All authority has been given to Me in heaven and on earth.

Go therefore and make disciples of all the nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit,

teaching them to observe all things that I have commanded you; and lo, I am with you always, even to the end of the age.” Amen.” Matthew 28: 18-20

Go therefore and make disciples of all the nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit,

teaching them to observe all things that I have commanded you; and lo, I am with you always, even to the end of the age.” Amen.” Matthew 28: 18-20

|

P.O.Box 74 Newlands 7725

Cape Town South Africa |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed