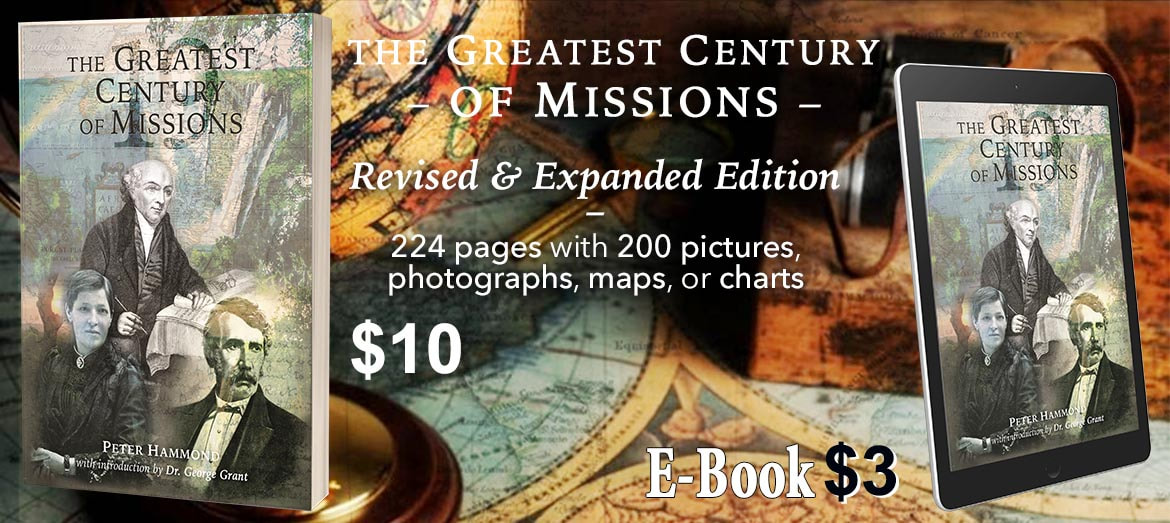

To see a video presentation on this article, click here To listen to an audio presentation on this article, click here Henry Martyn was born in Truro, Cornwall, England, and he was only two years old when his mother died from tuberculosis. (His sisters followed their mother to an early grave and by the time he was 28, he was the only member of his family still surviving.) Reclusive Student Henry was a gifted student, and the ease with which he was able to learn, tempted him to avoid hard work and he gained a reputation for idleness. He was not popular and his small physique invited bullying by other boys. To protect him from bullying, the teachers placed him under the protection of another boy, who had an enduring Christian influence on his life. Conversion While studying at St. John’s College, Cambridge, Henry got into arguments and fights. On one occasion he threw a knife at a fellow student. At this time his father died and his sister began intensive intercession for her wayward brother. A lecturer and another student challenged Henry about his relationship to the Lord, and he began reading The Bible. As Henry was converted to Christ, he also achieved great success in his academic studies, but now in the light of his conversion experience, Henry observed: “I obtained my highest wishes, but was surprised to find that I had grasped a shadow.”  Called to Missions His mind had been set on becoming a lawyer, but now the testimony of William Carey in India, and a book on David Brainerd, inspired Martyn to dedicate his life to missions. After graduating with high honours, and ordained as a Minister of the Church of England, he offered his services to the Church Missionary Society and was appointed Chaplain to British soldiers under the British East India Company. Henry set sail for India. Academic Evangelist He was an academic, who loved the seclusion of study. It was a perpetual struggle for him to bring himself to confront people, when he would prefer to be engrossed in books and languages. But, as he sought to be faithful to his duty, a passion to win souls to Christ was fanned into flame. Henry wrote: “Let me forget the world and be in a desire to glorify God”. Lydia Another complication in his missionary work was his devotion to Lydia Grenfell. He feared that his passion for her was akin to idolatry. Should he go to India with God, or remain in England with Lydia? Did his calling require him to remain unmarried? He feared it did. His friends advised him to set sail alone. It was with a heavy heart that he said goodbye to Lydia. They never saw each other again after he sailed, but her name appears in almost every page of his journal. Seizing the Cape en Route to Calcutta Henry set out as a Chaplain, meant to work amongst the British staff of the East India Company. He was expressly forbidden to engage in missionary work amongst the Indians. When he set sail in August 1805, it was as part of a British fleet transporting 5000 troops to invade the Cape of Good Hope, and seize it from the Dutch. En-route to the Cape, Henry engaged in counselling soldiers and comforting victims of dysentery on the ship. He saw the Cape captured in January 1806 before continuing his voyage to India. Many of the soldiers and sailors responded to his evangelistic efforts with indifference, opposition and ridicule. He came away from the conflict for the Cape convinced that it was Britain’s duty and destiny to evangelise the world, not to colonise it. “I prayed that England whilst she sent the thunder of her arms to distant regions of the world might not remain proud and ungodly at home but show herself great indeed, by sending forth the Ministers of her Church to diffuse the Gospel of peace.” Rejection and Opposition Arriving in Calcutta in May 1806, Martyn’s first sermon at St. Johns, evoked great antagonism. Martyn’s proclamation of basic Reformed doctrines was viciously attacked, even from the very pulpit. The coarse sights and sounds of heathen outrages committed daily on the streets, horrified Henry, who wrote: “If I had (the language), I would preach to the multitudes all the day, (even) if I lost my life for it.”  Chaplain to the Military As Henry was assigned to different military bases to serve as the chaplain to the troops, he also engaged himself in learning Hindustani and translating the book of Acts and Scripture tracts into the local language. His chaplaincy work at the local hospital was particularly effective, especially amongst the Hindu women. Evangelising Hindus The Europeans were critical of his ministry and thought it degrading that he should be troubled about the Indians. For their part, the Indians tended to hate him simply because he was an Englishman. If Henry had taken to heart the harsh opinions voiced concerning him, it is doubtful that he would have been able to achieve anything. Education and Translation By 1807, Henry had established five schools for Indian children, in and around Dinapor. He then translated the Book of Common Prayer into Urdu/Hindustani and concluded a commentary on The Parables of Christ. Each Sunday he conducted a service at 7:00am for the Europeans and at 2:00pm for the Hindus. Hospital visitation was a daily ministry. Devastating Disappointment and Despair But before the end of 1807, which saw so many great achievements in his ministry, two items of news from England plunged him into despair, the death of his eldest sister and Lydia’s refusal to his proposal for marriage. A year had passed since his letter proposing to Lydia had been mailed. Bible Translation and Conversions Henry poured himself into his ministry and by March 1808, he had completed his translation of the New Testament into Urdu/Hindustani. In 1809 he was appointed Chaplain at Cawnpore, a further 300 miles up the Ganges River. Here he had over 1000 soldiers to minister to. He also began to preach the Gospel in Hindustani publicly. An influential Sheik, who came to observe this strange sight, was won over by the Gospel. By 1810 he had established a congregation at Cawnpore. Duty and Delight Despite Disease Henry suffered ill health and wrote that he found preaching physically demanding. Studying was his delight, but public speaking was a burdensome duty: “It is the speaking that kills me.” Evangelising Muslims in Persia Martyn completed the translation of the New Testament into Persian and determined to go to Persia to test and improve his translation. As he turned 30 years old, Martyn set sail for Persia. Convinced that his Persian translation of the New Testament was of inferior quality, he set about to completely revise his translation. He was also involved in regular private and public arguments, in challenging and refuting the claims of Islam. He succeeded in making the Gospel a talking point amongst the highest authorities. The New Testament in Persian By the time he had completed the Persian New Testament, it was declared fit to be presented to the Shah himself. While attempting to gain an audience with the Shah at Tehran, Martyn was challenged with an ultimatum of declaring that: “Muhammad is the prophet of God.” Henry Martyn boldly refused and asserted instead that Jesus Christ is the Son of God. His opponents were enraged and threatened to have his tongue torn out for blasphemy. There were fears that his precious Book would be destroyed there and then. It was only by God’s grace that he escaped with his life and his translation. He later also completed the translation of the Psalms into Persian.  God’s Word Never Returns Void When Henry was again struck by fever, the Ambassador, Sir Gore Ousley, and his wife, nursed him back to health. Sir Gore himself presented the Scripture to the Shah. The Scripture was received with much gratitude and enthusiasm. The Shah wrote: “In truth through the learned and unremitted exertions of the Reverend Henry Martyn it has been translated in a style most befitting sacred Books. The whole of the New Testament is completed in a most excellent manner, a source of pleasure to our enlightened and august mind.” Missionary to Arabia Henry Martyn now intended to travel to Arabia, to complete a Bible translation into Arabic. However, his ill health as he contracted the plague forced him to return to England, and en-route he had the joy of seeing Mount Ararat, where “the whole Church was once contained … safe in Christ, I’d ride the storm of life, and land at last on one of the everlasting hills!” The Man Who Never Wasted an Hour Shortly after that, in North East Turkey, on 16 October 1812, the student they called “the man who never lost an hour” gained eternity. He had often been heard to pray: “Let me burnout for God!” “Who shall not fear You, O God, and glorify Your Name? For You alone are holy. For all nations shall come and worship before You. For Your judgements have been manifested.” Revelation 15:4 Dr. Peter Hammond This article was adapted from the first chapter of The Greatest Century of Missions book (224 pages with 200 photographs, pictures, charts and maps), available from Christian Liberty Books, PO Box 358 Howard Place 7450, Cape Town South Africa, Tel: 021-689-7478, Fax: 086-551-7490, Email: admin@christianlibertybooks.co.za, Website: www.christianlibertybooks.co.za.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

More Articles

All

Archives

December 2022

|

"And Jesus came and spoke to them, saying, “All authority has been given to Me in heaven and on earth.

Go therefore and make disciples of all the nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit,

teaching them to observe all things that I have commanded you; and lo, I am with you always, even to the end of the age.” Amen.” Matthew 28: 18-20

Go therefore and make disciples of all the nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit,

teaching them to observe all things that I have commanded you; and lo, I am with you always, even to the end of the age.” Amen.” Matthew 28: 18-20

|

P.O.Box 74 Newlands 7725

Cape Town South Africa |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed